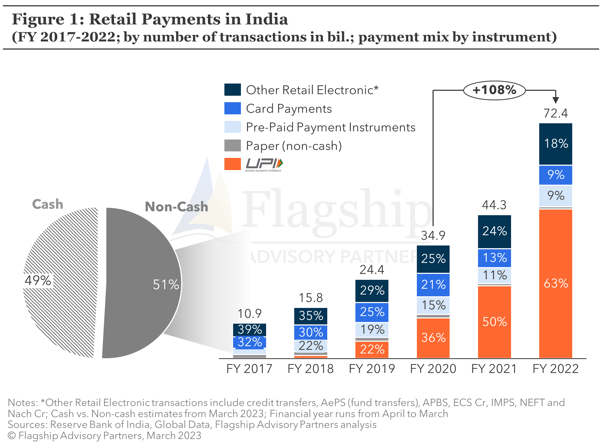

The Indian payments landscape completely transformed over the last decade, catalyzed by a shift from cash, cards, and other traditional payment methods to real-time A2A payments, powered by the UPI network and mobile apps. This globally-relevant case study on fintech innovation and disruption was fueled by a crescendo of forces including government policies, banking infrastructure upgrades, and the influence of mobile phone technologies. Figure 1 shows the rapid ascent of UPI-powered mobile payments while usage of cash, cards, and prepaid wallets diminished in share of wallet. Within this article, we tell the story of the rapid transformation of payments in India, and what the future might hold.

Mobile Payments Disruption

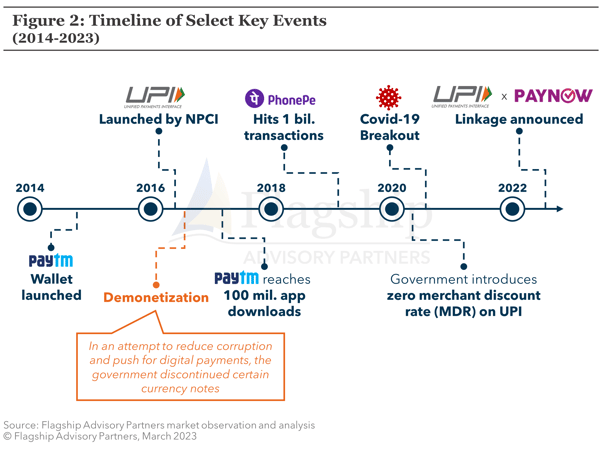

Prior to UPI, Indian fintechs were already driving the market towards mobile payments, a push that started with the introduction of digital wallets powered by prepaid accounts such as the Paytm Wallet in 2014. These mobile wallets were propelled by India’s demonetization policy, a large scale macro-economic exercise implemented by the government to combat corruption and push for digital payments. In November 2016, the government of India discontinued the acceptance of all existing currency notes overnight (larger than Rs. 500), with the motive of replacing them by printing new notes. The policy led to a shortage of cash in the country forcing consumers to find digital alternatives. This created the perfect opportunity for fintechs such as Paytm to fill this gap by offering digital propositions designed for both consumer and merchant. Digital wallet adoption rate skyrocketed as consumers became more comfortable with mobile payments.

UPI Payments Explained

The introduction of UPI turbo-charged the pace of innovation and disruption in India. Unified Payments Interface or UPI, launched by the National Payments Corporation of India (established by the Reserve Bank of India) in 2016, is an account-to-account payment system that enables consumers and merchants to send and receive payments with real-time settlement. Currently UPI accounts for about two in every three retail non-cash transactions in India.

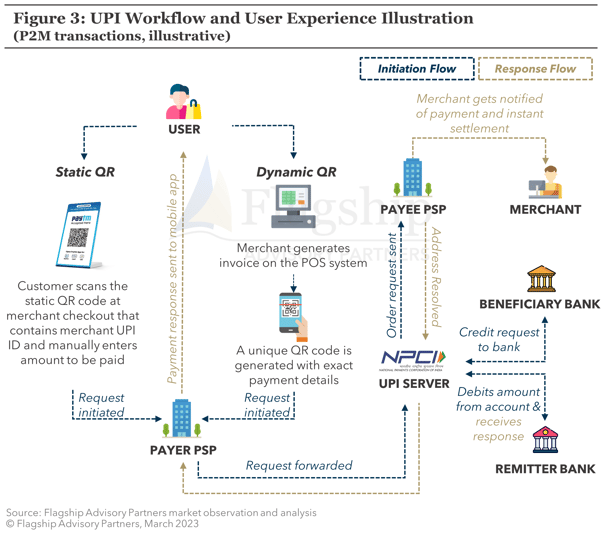

UPI is not an end-user product (not a mobile app), but a payment network, used by fintechs and banks who develop and distribute the mobile apps that power payments through the UPI network. Users can easily enable this payment method by creating a unique UPI identification key that is linked with the user’s bank account and mobile number. Many mobile payment apps such as PhonePe, GooglePay, and Paytm (among others) support UPI sign-up, initiation or receipt of payments to and from users’ bank accounts. For P2P transactions, users can simply use the mobile number linked with a UPI ID to transfer money instantly making the user experience extremely quick and frictionless.

Figure 3 illustrates the primary use cases for C2B (merchant) payments, which are enabled by QR codes. There are two types of QR codes used with UPI: Dynamic QR and Static QR. Larger merchants that have integrated payments at their point-of-sale, will utilize the dynamic QR code, which is generated upon billing and presents the customer with the exact amount to be paid. As software embedded payments are still relatively nascent in India, and limited to larger enterprises, static QR codes provide a simpler way for small merchants to receive payments without having an integrated POS system. The static QR only contains the UPI ID of the merchant and customer needs to manually input the amount to be paid. The key success factor for achieving a frictionless experience is that UPI transactions are real-time, allowing both consumers and merchants to receive instant notification of payment completion.

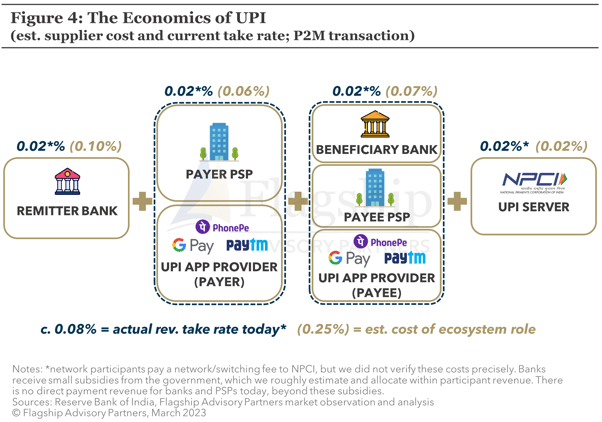

Government Incentive and The Real Cost of UPI

UPI’s rapid growth as a preferred means of C2B payments is fueled in part by a government policy for zero-cost UPI payments, which today, are free for both consumers and merchants (a policy introduced on 1 Jan 2020). The government does subsidize market participants, but this subsidy is small in comparison to the actual costs of the ecosystem (subsidies of c.$295 million in 2022 to merchant acceptance participants falls vastly short of the estimated total costs that are in excess of $1 billion). In the recently announced Budget for FY 2023-2024, the government reduced the subsidy amount to less than $200 million. According to ecosystem cost estimates from the Reserve Bank of India (RBI), on average, a C2B UPI transaction generates a total cost of approximately 0.25% considering the roles of the different stakeholders in the value chain. We break-down RBI’s cost estimates in Figure 4.

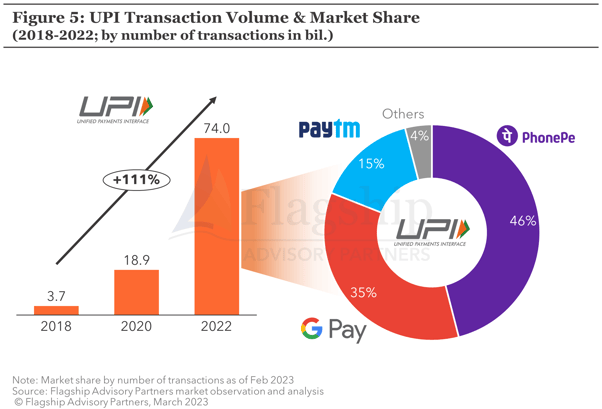

Due to India’s current zero-merchant-discount-rate policy, UPI C2B payments are unusually unprofitable for fintechs and banks. PSPs and app providers such as PhonePe, GooglePay, and Paytm (shares shown in Figure 5) are forced to find other sources of revenue such as bill payments and most notably, various forms of embedded credit to consumers and merchants. The lack of payments profitability is one reason why fintechs such as Paytm still struggle to achieve profitability. Paytm reported a -30.5% EBITDA margin for FY 2022, despite its scale and relatively long tenure in the market. The company did however, report a positive EBIDTA margin of c. 1.5% for the first time in Q3 FY 2023, which is attributed largely to expense reductions.

Some Indian market participants expect the ‘zero-cost’ policy to fade, resulting in more natural economic incentives for parties involved in C2B UPI transactions. Merchants continue to lobby in favor of the current policy, which seems to be working as the Indian Ministry of Finance announced last year that UPI is a digital good and the government has no intension of changing the current zero-cost policy. For now, there remains a tension between the massive fintech potential of UPI and the lack of payments profitability for UPI service providers.

Growth of Mobile Payments and Future Implications

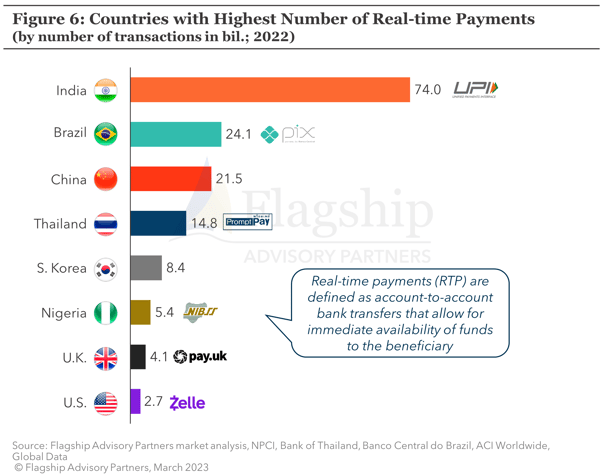

India is now the global market leader for real-time A2A payments, but certainly not the only country which has seen a massive uptake in digital payments, as shown in Figure 6. This trend is replicated in other markets such as Brazil and Thailand, where A2A banking infrastructure combined with mobile means of payment are powering disruption. We do not see the same pace of A2A + mobile disruption in more mature western markets. This is a classic example of the ‘leapfrog effect’ in payments where less-developed markets evidence far more rapid innovation and disruption versus mature markets, where behaviors linked to cards are more deeply entrenched (formed over decades).

Countries around the world are drawn to the India (UPI) case study as they aspire for efficient, digital payments and alongside financial inclusion. The National Payments Corporation of India (NPCI) is working to internationalize UPI, recently signing a memorandum of understanding with 13 countries including Singapore, Thailand, France, Netherlands and the U.K. to enable acceptance of UPI outside the countries. NPCI is working with payment providers such as Worldline in Europe to implement Indian payment methods including RuPay and UPI in countries including Netherlands, Belgium and Switzerland. Through this partnership, Worldline’s merchants in Europe will be able to accept UPI payments at the point-of-sale using QR codes.

The Reserve Bank of India also recently announced an agreement with the Monetary Authority of Singapore allowing interoperability between UPI and PayNow (Popular alternative payment method in Singapore). This allows users of both instant payment systems to use the other seamlessly without additional sign-ups and send money cross-border. This alliance is a unique global case study on interoperability of A2A schemes, and one which we expect to be replicated in other markets.

India is a perfect example of the power of fintech to transform an economy and the day-to-day lives of people. In less than a decade, India went from a wide-spread lack of financial inclusion to a country that is now leading the world in A2A-powered mobile payments. This success is the result of government policy working hand-in-hand with banking and fintech innovation. Going forward, however, the fintech community must tackle challenges posed by zero-cost payments, as while Indian consumers and merchants benefit from payments innovation, shareholders are still searching for return on investment.

Please do not hesitate to contact Joel Van Arsdale at Joel@FlagshipAP.com with comments or questions.