The Wall Street Journal’s reporting on Nov. 28 that “Apple is pulling the plug on its credit-card partnership with Goldman Sachs” caps off months of highly public news about the dissolution of Goldman’s entry into consumer financial services. In this article, Flagship estimates the profitability of the Apple Card program, which we believe is the root cause of the situation: the fundamental construction of the program is simply not profitable for Goldman, and Goldman, due to its desire to enter into consumer financial services with a marquee brand, likely agreed to partnership terms with Apple that restrict its ability to return the program to profitability.

Background

In March 2019, tech giant Apple teamed up with Goldman Sachs as its banking partner to venture into consumer credit card issuing with the launch of the Apple Card. For Apple, the Apple Card marked a further push into services, seeking to diversify its revenue streams beyond hardware sales. For Goldman Sachs, the partnership was the cornerstone of Goldman’s entry into consumer financial services. After launching in August 2019, the Apple Card quickly gained traction in the market. While some pundits panned the card as topical improvements rather than true innovation that lived up to the hype, the card was unquestionably a success with consumers due to the brand cache of Apple, the card’s front and center placement in Apple Wallet, a straightforward application process, no fees, and some innovative UX/UI tweaks (e.g., a wheel graphic to set payment amounts).

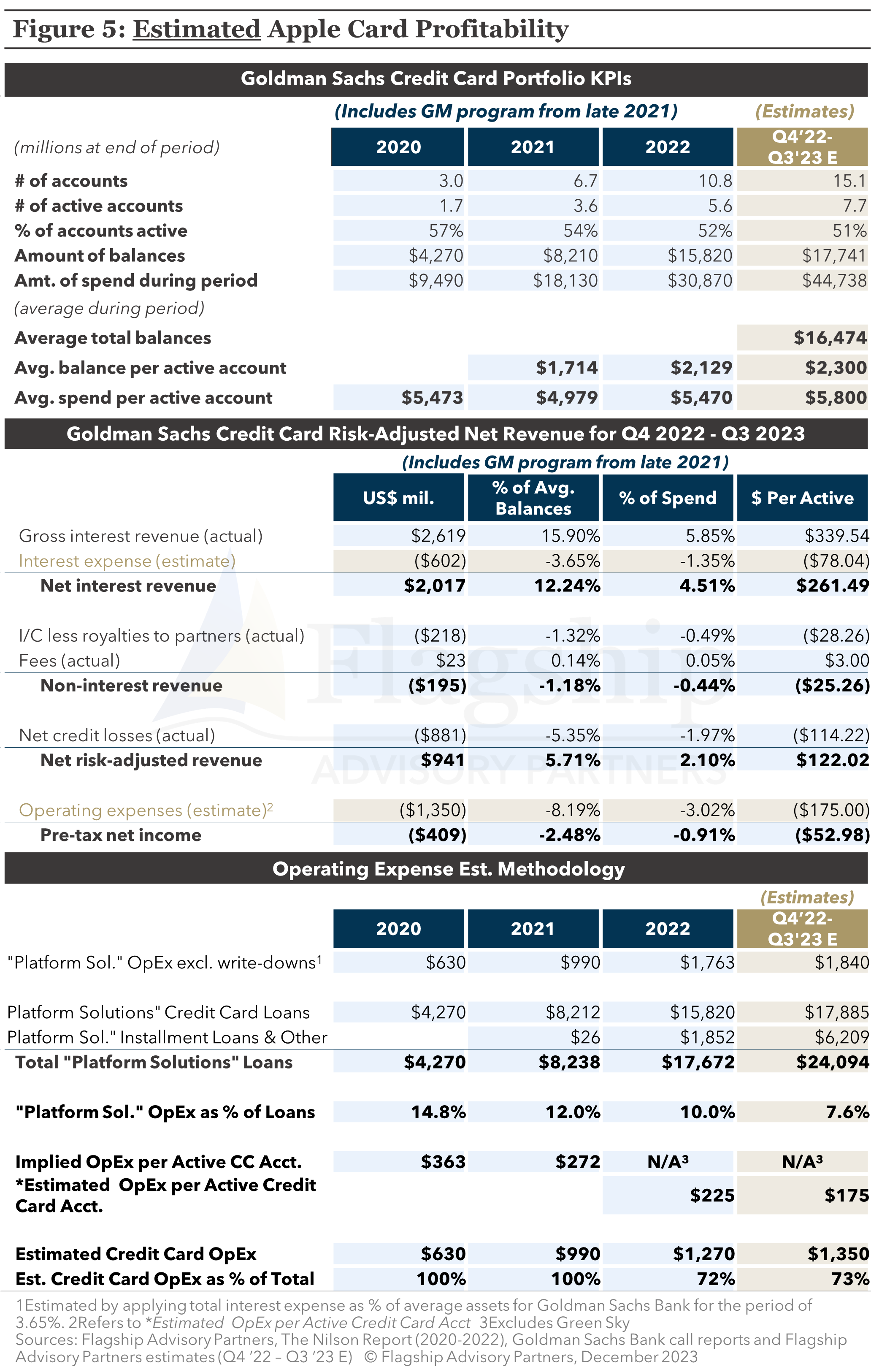

While popular among consumers, the Apple Card had several challenges. These included atypical operational design and pricing requests from Apple, aggressive underwriting requirements, and subsequently, profitability challenges for Goldman Sachs. Despite these discouraging partnership data points, in October 2022 Goldman reportedly doubled down by renewing the consumer-finance partnership through to 2029. However, within the following year, Goldman seemingly began to regret the renewal as reports of Goldman wanting out began to surface in the Spring of 2023. Goldman’s wishes are soon to be granted per Wall Street Journal’s report in late November 2023 stating that Apple is pulling the plug on the Goldman credit card partnership. Apple reportedly proposed a withdrawal plan to take effect within an estimated 12 to 15 months, which includes the full scope of Apple and Goldman’s consumer finance partnership (the credit card and savings account initiative launched in early 2023). Information about the succeeding issuer of the Apple card is unavailable at the present time. Refer to the full partnership timeline below (Figure 1).

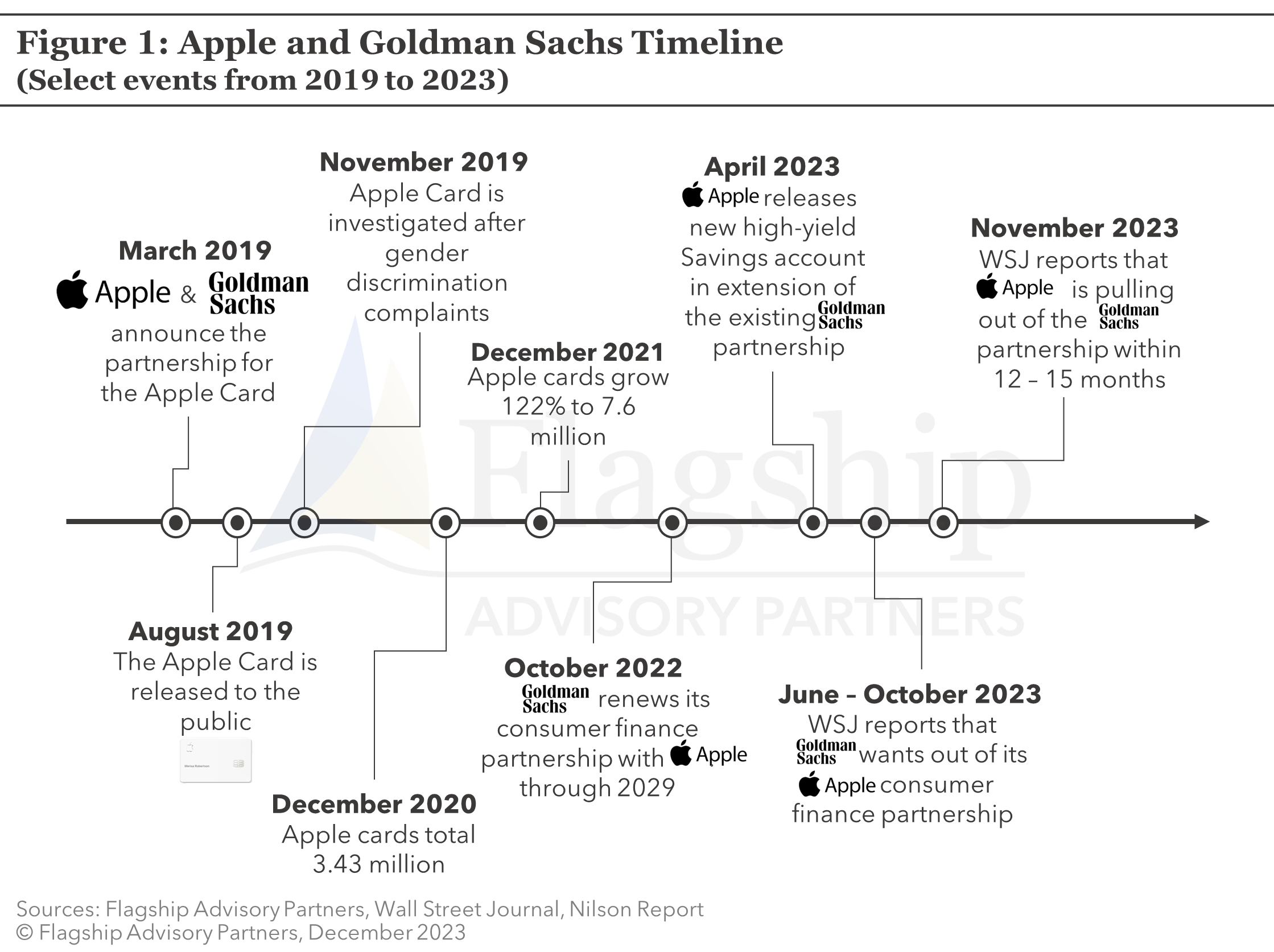

A little over one year after launching, Apple cards totaled 3.43 million1 at the end of 2020 and, within the following year, the number of cards grew 122% to 7.6 million2 at the end of 2021. However, in the subsequent year, growth slowed to 58% in 2022. Despite slowing growth rates, Flagship estimates that the Apple Card has penetrated 18% of its potential addressable customer base (under-writable adults in the US), which is a significant achievement relative to other tenured co-brand programs (see Figure 2 below).

Challenges

The Apple-Goldman partnership has faced its share of (highly public) challenges and controversies. Ahead of its launch, Apple was reported to have made significant demands, which subsequently led to profitability, risk management, and operational problems. We delve into the operational design, pricing, and underwriting standards issues below.

Operational Design

Apple requested a suite of unusual operational designs that included billing statements that align with the calendar month (rather than staggered billing cycles to spread out the operational load of inbound calls), instant cash-back rewards, and the design of the physical card.

Pricing

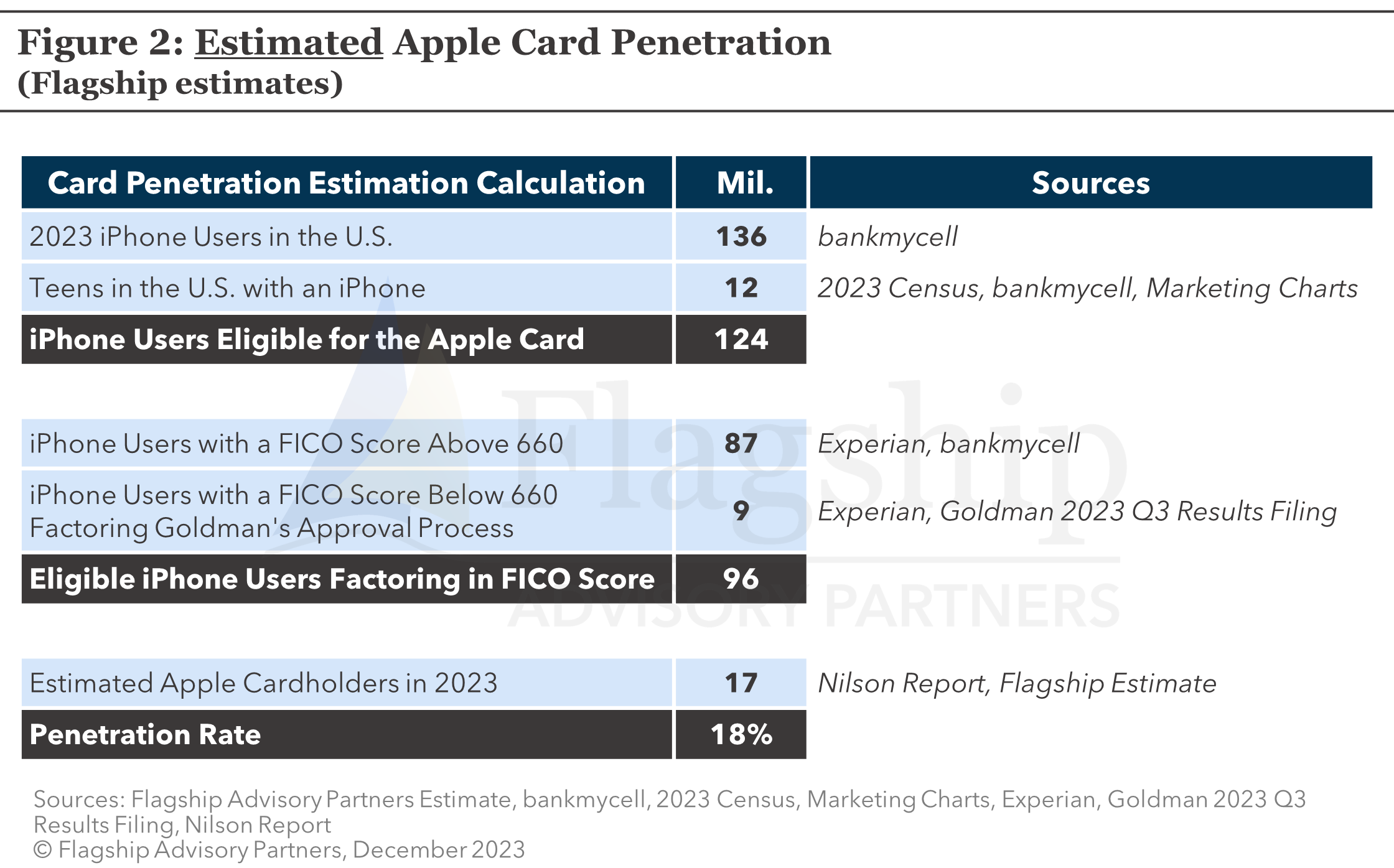

In addition to the operational design requests, Apple atypically requested a literally no-fee card, meaning a lack of chargeable fees (such as annual, late, over-limit, and foreign transaction fees). For comparison purposes, in Figure 3 below we briefly illustrate how the Apple Card stacks up with similar cards from top US issuers.

The Apple Card has a competitive value proposition, although the card’s rewards feature primarily appeals to consumers who regularly utilize Apple Pay. Notably, utilizing the Apple Card for traditional e-commerce transactions, where physical point-of-sale terminals are bypassed, and the merchant does not allow for Apple Pay checkout, does not result in reward accrual, and given the high penetration of e-commerce in the US, is meaningful. Another attractive (to consumers), yet odd from the perspective of issuers, standout feature is the card’s comprehensive fee-free structure, notably the absence of late fees. Late fees are typically utilized by credit card issuers to encourage timely payments and serve as a means of risk mitigation and revenue generation.

Underwriting Standards

As a result of (relatively) aggressive underwriting standards, Goldman has experienced comparably high credit loss rates. In 2022, Goldman’s net loss rate on credit cards was 3.46%3, which was nearly double that of competitors like JPMorgan (1.47%3) and Bank of America (1.60%3). As overall credit card loss rates rise, Goldman continues to feel the heat as its loss rate rose to 6.2% in Q3 2023.

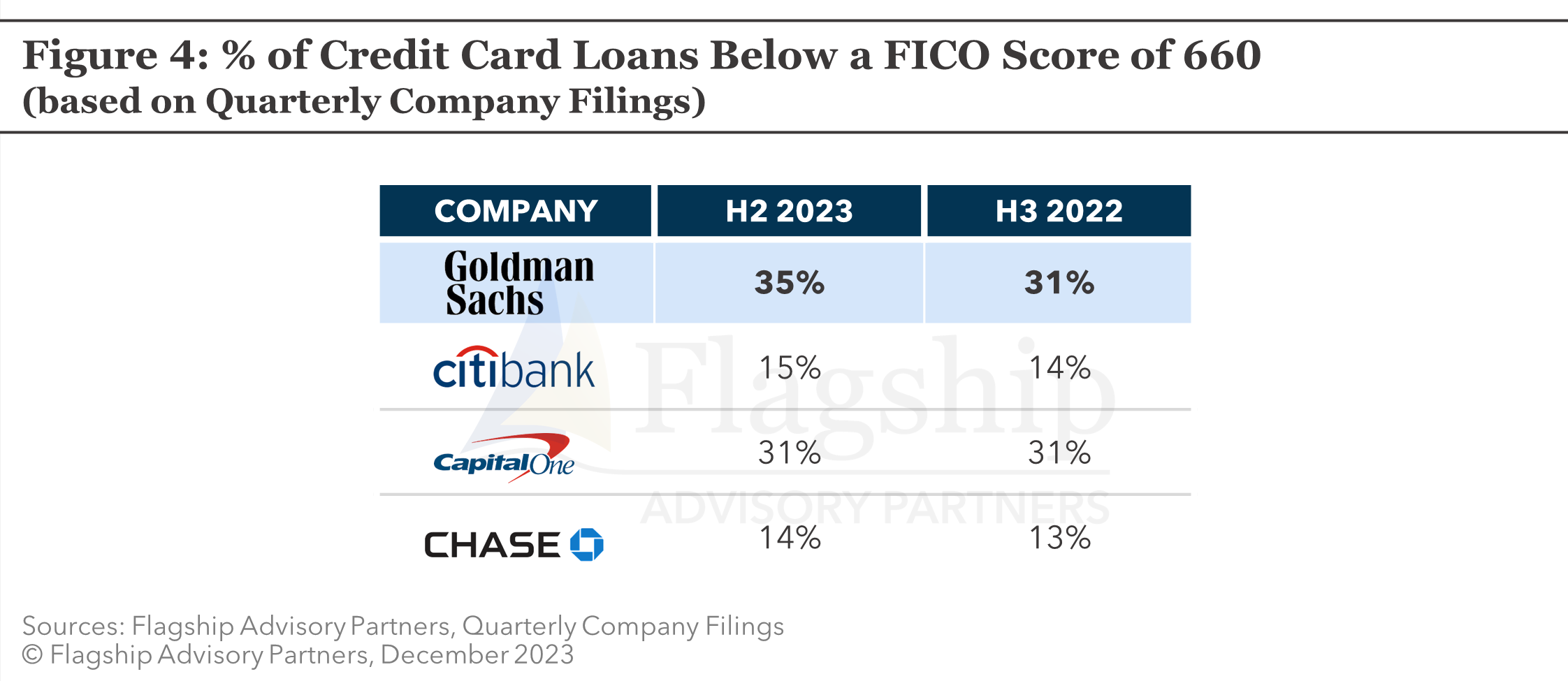

Among other market factors, a likely culprit of such a high loss rate: the composition of Goldman’s credit loans. Goldman’s 2022 Q2 Report shows that more than a quarter of Goldman’s card loan balances have gone to customers with a FICO score below 660. This number continued to rise to 35% per Goldman’s 2023 Q3 Report, which is much higher than competitors (see Figure 4). Editorial note for our readers less familiar with the US credit system: FICO scores are standardized credit scores based on credit-bureau data aggregated on most US consumers and are commonly used by US lenders as an industry-standard input and comparative tool to assess an individual’s credit risk. The scores range from 300 to 850, with scores above 660 considered good to exceptional, leading to an increased likelihood of approval, and scores below 660 considered fair to very poor, leading to a lowered likelihood of approval.

In addition to aggressive underwriting impacting credit loss rates, reports about gender bias in Goldman’s credit approval process surfaced, leading to an investigation by the New York Department of Financial Services. Both Apple and Goldman pledged to address the issue and ensure fair treatment for all applicants.

Poor Profitability

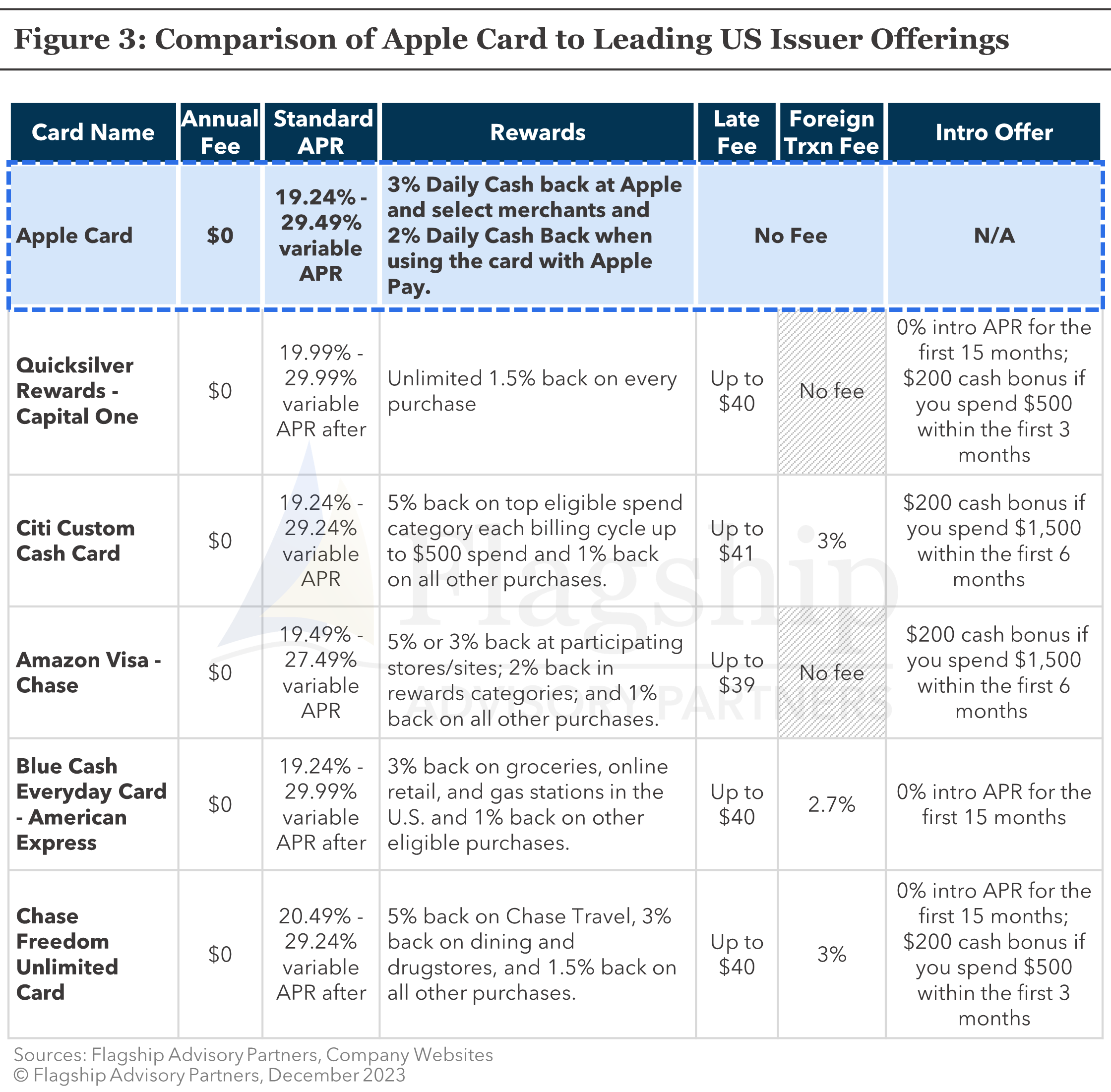

The combination of a substantial portion of Goldman’s clientele holding a FICO score below 660 coupled with the absence of late fees, forms a potent catalyst for impacting Goldman’s earnings—and it did. Flagship estimates that Goldman will incur a pre-tax loss on the Apple Card program of approximately $500 million in Q4 2022 – Q3 2023 (refer to Figure 5).

Lessons Learned

The Apple / Goldman sags is instructive for several reasons:

- Brands, the “cool factor”, and UX matter, even in payments and fintech. While traditional institutions often scoff at new products (e.g., “BNPL is just a credit card”, “Apple only tweaked the optics”), customers see it differently. Only Apple could power what is arguably a decent, but not outstanding, cash-back rewards card, to approx. 15 million accounts and penetrate 18% of its eligible user base within 4 years.

- Underwriting tech evolves, but credit risk principles don’t. While many issuers and fintechs tout the benefits of advanced models and data sources for underwriting, core predictive elements are relatively constant. Sub-prime underwriting is going to result in higher credit losses, no matter how you do it, as Goldman learned the hard way.

Mass market consumer credit card issuing in the U.S., while a huge TAM, is not easy to penetrate and still maintain profitability. Goldman is a large FI and invested heavily, and while it (arguably) made some questionable decisions when negotiating its partnership with Apple, it was never able to achieve the scale and expense efficiencies necessary to compete with the large U.S. mega-issuers. - Unit profitability matters, no matter how much scale you have. Even if Goldman was able to scale up efficiently enough to compete on operating expenses, constructing a card program with a competitive interest rate, no fees, aggressive underwriting, and high royalties to a partner was always going to be challenging (or more pessimistically, near impossible).

- Partnerships need to be balanced, and sometimes it’s better to just say “no”. As a well-funded, eager new entrant into consumer financial services, Goldman bid too aggressively to win the Apple partnership. It arguably gave away too much, not only in terms of partnership economics to Apple, but also in influence over underwriting standards, features/functionality, and pricing decisions. While we can debate the wisdom of bank regulators’ and executives’ conservatism at times, that level of conservatism is fundamentally due to good reasons: unsecured lending to consumers is difficult and risky. Fortunately for Goldman, the parent is able to absorb these losses. Smaller fintechs would simply go under. From Apple’s perspective, the outcome is also poor. Getting a good deal in a partnership negotiation can quickly become a Pyrrhic victory, because if partnership economics and control become unbalanced and one partner continues to lose money, the entire program suffers (from lack of investment, lack of motivation, and disruption from dissolution of the partnership). Moreover, Apple can likely be certain that future potential partners will have learned from Goldman’s lessons, and we speculate that the next deal that Apple gets will be worse than if it had struck a more balanced deal with Goldman. The math on getting a great deal, have it fall apart early, then getting a restrictive deal, is probably on average worse for Apple than if it had struck a more balanced deal with Goldman in the first place.

It will be interesting to see what happens next. Apple will certainly find a new partner given the power of its brand, and it will likely be one of the mega-issuers (Citi, Amex, Bank of America, Chase, etc.). Apple’s deal will be worse, and the card program will look more like other co-brands, and the program will still be big. Some intangible pre-bubble “sparkle” will go out of the industry, but like the latest version of the iPhone that carries only marginal improvements but is still cool enough that customers buy a new one more often than they arguably need, U.S. consumer credit card lending will march on.

Please do not hesitate to contact Joel Van Arsdale at Joel@FlagshipAP.com with comments or questions.

[1)Top Issuers of General Purpose Credit Cards in the US.” Nilson Report, no. 1192, 28 Feb. 2021

[2)Top Issuers of General Purpose Credit Cards in the US.” Nilson Report, no. 1214, 28 Feb. 2022

[3) Calculated by Flagship as total 2022 credit card gross credit losses less recoveries divided by average quarterly balances for the four quarters of 2022 from Goldman Sachs Bank call reports